Givinostat: A Breakthrough in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Treatment and the Future of DMD Therapy

Abstract

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is a severe genetic disorder characterized by progressive muscle degeneration due to mutations in the DMD gene, which leads to the absence of functional dystrophin. The disease results in chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and loss of mobility, significantly reducing life expectancy. Traditional treatments, such as corticosteroids, provide symptomatic relief but come with severe side effects. Givinostat, a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, has emerged as a promising therapy that directly targets the pathological mechanisms of DMD. By modulating gene expression, reducing inflammation, and promoting muscle regeneration, Givinostat has demonstrated significant clinical benefits in slowing disease progression. Unlike gene therapy and exon-skipping treatments, which are mutation-specific, Givinostat is a mutation-independent therapy, making it accessible to a broader range of patients. Clinical trials, including the Phase 3 EPIDYS trial, have confirmed its efficacy in improving muscle function, reducing fibrosis, and preserving ambulation in children aged six and older. As research advances, combination therapies involving Givinostat, gene editing, and exon-skipping drugs may further enhance treatment outcomes. This article explores the mechanism, benefits, and future potential of Givinostat as a game-changing approach to managing DMD.

Understanding Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is one of the most severe and common genetic muscle disorders, affecting approximately 1 in 3,500 to 5,000 male births worldwide. It is a progressive neuromuscular disease caused by mutations in the DMD gene, which encodes dystrophin, a crucial protein responsible for maintaining muscle fiber integrity. The absence of functional dystrophin leads to progressive muscle degeneration, inflammation, and fibrosis, ultimately causing severe disability and premature death. Children with DMD typically begin showing symptoms between the ages of 2 and 5 years, such as delayed motor milestones, difficulty running, frequent falls, and an abnormal gait. As the disease progresses, affected individuals experience progressive muscle weakness, which eventually leads to the loss of ambulation, usually by their early teens. Beyond skeletal muscle deterioration, DMD also affects cardiac and respiratory muscles, resulting in cardiomyopathy and respiratory insufficiency—two leading causes of mortality in DMD patients. One of the hallmark pathological mechanisms of DMD is chronic inflammation and impaired muscle repair. Due to continuous muscle damage, inflammatory cells infiltrate the affected tissues, triggering a cycle of immune activation and fibrosis. Additionally, muscle satellite cells, which play a crucial role in regeneration, fail to function effectively, leading to muscle wasting. Over time, damaged muscle fibers are replaced with fat and fibrotic tissue, further impairing muscle function. While there is no cure for DMD, current treatments aim to slow disease progression and improve quality of life. Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and deflazacort, are the standard treatment for delaying muscle degeneration, although they come with significant side effects. Recently, gene therapies, exon skipping drugs, and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors like Givinostat have emerged as promising new strategies to address the complex pathology of DMD. These treatments hold potential for not only preserving muscle function but also modifying disease progression, offering new hope to patients and families affected by this devastating disorder.The Science Behind Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) and Its Role in DMD

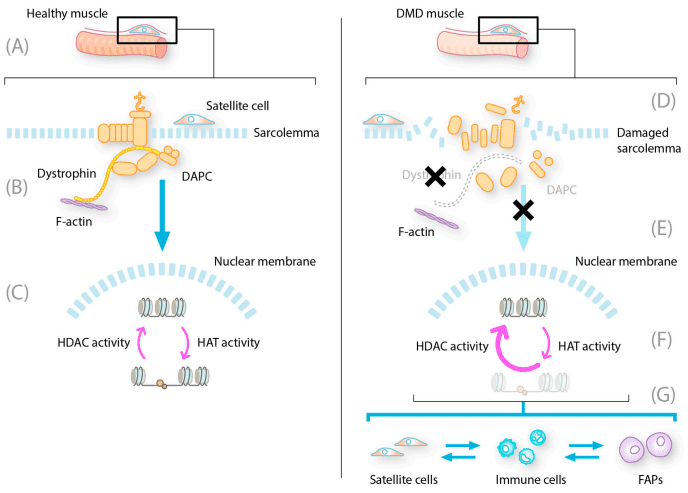

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is not only a genetic disorder but also an epigenetic disease, where changes in gene expression contribute to disease progression. One of the major players in this process is histone deacetylase (HDAC), a group of enzymes that regulate gene expression by modifying chromatin structure. HDACs remove acetyl groups from histone proteins, leading to chromatin condensation and suppression of gene transcription. In DMD patients, HDACs are hyperactivated, exacerbating muscle degeneration by inhibiting the expression of genes responsible for muscle regeneration and repair. The absence of dystrophin, the protein affected in DMD, triggers chronic inflammation and fibrosis, further impairing muscle repair. One major consequence of HDAC overactivity is the suppression of myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), such as MyoD and MEF2, which are crucial for muscle stem cell activation and differentiation. Without proper MRF activity, muscle satellite cells fail to regenerate damaged muscle fibers, leading to progressive muscle loss. Moreover, HDAC hyperactivity influences the immune response in dystrophic muscles. Chronic inflammation in DMD leads to a persistent presence of pro-inflammatory macrophages, preventing muscle healing. HDACs regulate the balance between pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages, and their excessive activity skews this balance towards a pro-inflammatory state, worsening fibrosis and muscle damage. Another critical aspect of HDAC involvement in DMD is its effect on fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs)—a population of stem cells that can either support muscle repair or contribute to fibrosis and fat accumulation. When HDACs are overactive, FAPs differentiate into fibroblasts and adipocytes instead of assisting muscle regeneration. This process promotes excessive connective tissue (fibrosis) and fat infiltration, accelerating disease progression.

FIGURE 1. Constitutive HDAC activity contributes to dystrophic muscle pathology.

Given these pathological effects, HDAC inhibitors have emerged as promising therapeutic agents for DMD. By blocking HDAC activity, these drugs aim to restore muscle repair mechanisms, reduce inflammation, and prevent fibrosis—paving the way for more effective treatment strategies.Givinostat: The Multi-Targeted Approach to Treating DMD

Givinostat is an orally administered histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor designed to target multiple pathological mechanisms involved in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). Unlike traditional treatments that mainly focus on symptom management, Givinostat addresses the underlying disease mechanisms by modulating gene expression, reducing inflammation, and enhancing muscle regeneration. One of the primary effects of Givinostat is its ability to counteract HDAC overactivity, which is a key factor in DMD progression. In dystrophic muscles, excessive HDAC activity inhibits muscle stem cell differentiation and contributes to chronic inflammation and fibrosis. By blocking HDAC enzymes, Givinostat reactivates genes essential for muscle repair, allowing muscle satellite cells to regenerate new fibers and preventing fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs) from transforming into fibrotic and fat tissue. In addition to promoting muscle regeneration, Givinostat has been shown to modulate the immune response in dystrophic muscle tissue. Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of DMD, driven by an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory immune cells. By inhibiting HDACs, Givinostat reduces the activity of pro-inflammatory macrophages while enhancing the function of regulatory immune cells, which helps decrease fibrosis and muscle degeneration. Several preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of Givinostat in slowing down disease progression. In animal models, Givinostat treatment resulted in increased muscle fiber diameter, reduced fibrosis, and enhanced muscle function. Phase 2 clinical trials in DMD patients showed improvements in muscle structure and function, leading to a significant delay in disease progression compared to placebo groups. The Phase 3 trial (EPIDYS) further confirmed its benefits, showing that Givinostat significantly improved motor function, reduced muscle fat infiltration, and preserved mobility in patients aged six years and older. As an FDA-approved therapy, Givinostat represents a new era in DMD treatment. Unlike steroids, which come with severe side effects, Givinostat provides a more targeted, multi-faceted approach to managing the disease, offering new hope for patients and families.Comparing Givinostat with Other DMD Treatments

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) remains an incurable disorder, but several therapeutic strategies have emerged to slow its progression and improve the quality of life for patients. Givinostat, an HDAC inhibitor, offers a multi-targeted approach that distinguishes it from existing treatments like corticosteroids, gene therapies, and exon-skipping drugs. Understanding how these treatments compare can provide insights into the future of DMD management. Givinostat vs. Corticosteroids Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and deflazacort, have been the standard of care for DMD for decades. They work by reducing inflammation and stabilizing muscle strength, delaying loss of ambulation. However, long-term steroid use is associated with severe side effects, including growth retardation, osteoporosis, weight gain, insulin resistance, and mood changes. Givinostat, on the other hand, offers an alternative by modulating gene expression, reducing inflammation, and promoting muscle repair without the severe side effects of steroids. Givinostat vs. Gene Therapy Gene therapy, such as micro-dystrophin gene replacement therapy, aims to deliver a functional dystrophin gene using viral vectors. While promising, these therapies are limited by immune response issues, delivery challenges, and partial restoration of dystrophin. Unlike gene therapy, which is mutation-specific, Givinostat is mutation-independent and can benefit all DMD patients, making it a broader therapeutic option. Givinostat and Exon-Skipping Therapies Exon-skipping drugs like eteplirsen, golodirsen, and casimersen target specific mutations to restore partially functional dystrophin. These treatments only work for a subset of patients with eligible mutations, whereas Givinostat offers benefits regardless of genetic mutation. However, combination therapy using exon-skipping and Givinostat may provide synergistic benefits, as HDAC inhibition has been shown to enhance dystrophin expression in preclinical models. Future of Combination Treatments Given their complementary mechanisms, combining Givinostat with gene therapy or exon-skipping drugs could enhance treatment efficacy. As new research emerges, a multi-drug approach may become the standard in DMD management, offering longer-lasting functional improvements.The Future of DMD Treatment: What Lies Ahead?

As research continues to advance, the future of DMD treatment is shifting toward more personalized and combination therapies. The approval of Givinostat by the FDA marks a significant milestone, but ongoing studies are investigating how it can be optimized with other therapeutic approaches to further improve outcomes. Regulatory Progress and Global Accessibility Currently, Givinostat is approved in the U.S. for patients aged six and older, but the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is still evaluating its use. Expanding access to other countries will be crucial in making this therapy available to a larger population of DMD patients. Challenges and Unanswered Questions Despite its promise, questions remain regarding: Long-term effects of HDAC inhibition on muscle function and overall health. Effectiveness in younger patients (under six years old). Potential side effects with prolonged use, such as gastrointestinal discomfort and thrombocytopenia. The Rise of Combination Therapies The next phase of DMD treatment may focus on combination therapies that pair Givinostat with: Gene therapy (e.g., micro-dystrophin gene therapy) to restore dystrophin while improving muscle health. Exon-skipping drugs to boost dystrophin expression alongside HDAC inhibition. Anti-inflammatory and fibrosis-targeting drugs to further slow muscle degeneration. New Innovations in Muscle Regeneration Recent research is also exploring stem cell-based approaches and gene-editing technologies like CRISPR to provide permanent genetic corrections for DMD. While these therapies are still in development, their potential integration with Givinostat could significantly improve long-term muscle function. Final Thoughts Givinostat represents a pivotal step forward in the treatment of DMD, offering a new hope for patients and families affected by this devastating disease. While challenges remain, continued research and the development of personalized treatment combinations will likely define the next decade of DMD therapy.References

- Aartsma-Rus, A., Ginjaar, I. B., & Bushby, K. (2016). The importance of genetic diagnosis for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of Medical Genetics, 53(3), 145–151. DOI

- Dowling, P., Swandulla, D., & Ohlendieck, K. (2023). Cellular pathogenesis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Progressive myofiber degeneration, chronic inflammation, reactive myofibrosis and satellite cell dysfunction. European Journal of Translational Myology, 33(2), 11856. DOI

- Duan, D., Goemans, N., Takeda, S., Mercuri, E., & Aartsma-Rus, A. (2021). Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 7(1), 13. DOI

- Mercuri, E., Vilchez, J. J., Boespflug-Tanguy, O., Zaidman, C. M., Mah, J. K., Goemans, N., et al. (2024). Safety and efficacy of givinostat in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (EPIDYS): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Neurology, 23(4), 393–403. DOI

- Licciardi, P. V., & Karagiannis, T. C. (2012). Regulation of immune responses by histone deacetylase inhibitors. ISRN Hematology, 2012, 690901. DOI

- Mozzetta, C., Sartorelli, V., & Puri, P. L. (2024). HDAC inhibitors as pharmacological treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A discovery journey from bench to patients. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 30(3), 278–294. DOI

- Aartsma-Rus, A. (2025). Histone deacetylase inhibition with givinostat: A multi-targeted mode of action with the potential to halt the pathological cascade of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 12, Article 1514898. DOI