The Role of EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor) in the Construction of Organoid Models

Abstract

Abstract: Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) plays a crucial role in the construction and maintenance of organoid models, which are three-dimensional in vitro structures mimicking human organs. EGF supports key processes in organoid development, including cell proliferation, stem cell renewal, differentiation, and morphogenesis. This growth factor is integral to maintaining the structural integrity and functionality of organoids, ensuring they replicate the complex characteristics of real tissues. EGF’s impact varies across different organoid models, including those representing the brain, liver, intestines, and lungs. The use of EGF in organoid research has significant implications for drug discovery, disease modeling, and personalized medicine, offering a more accurate platform for testing therapies and understanding human biology.

Introduction

Organoid models have revolutionized biomedical research, offering researchers a dynamic, in vitro representation of human tissues and organs. These miniaturized organ systems replicate key aspects of their native counterparts, including architecture, cellular diversity, and functionality. Their ability to mimic real biological processes has opened doors for studying development, disease mechanisms, drug screening, and personalized medicine. One of the critical components involved in the creation and maintenance of these organoid models is Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF). In this blog post, we will explore the role of EGF in constructing organoid models, why it is essential, and how it influences the growth, differentiation, and function of organoids.

What Are Organoids?

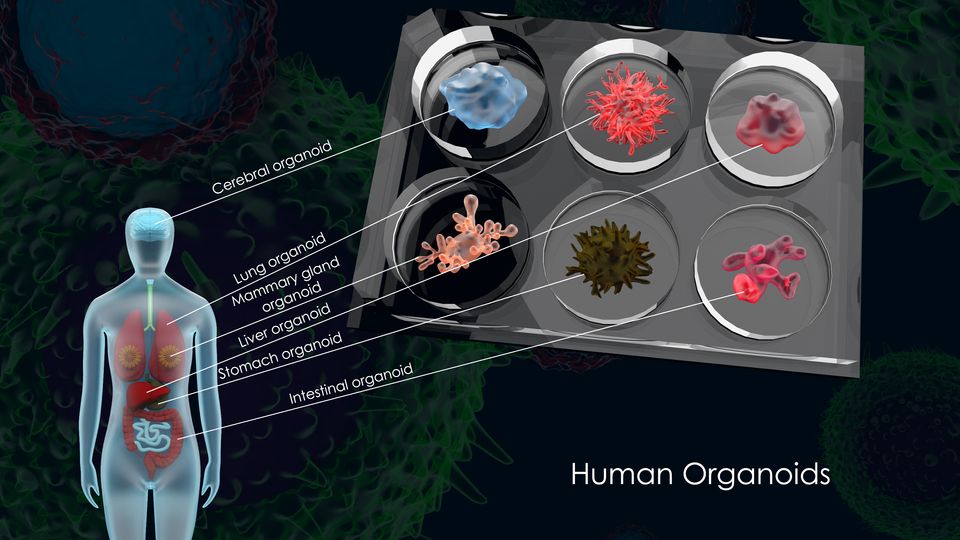

Organoids are three-dimensional clusters of stem cells that self-organize into structures resembling real organs. They are derived from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), adult stem cells, or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), depending on the model. Organoids can be developed to represent various organs, including the brain, liver, intestines, kidneys, and lungs. The growth of organoids in a controlled environment allows for the study of cellular interactions, disease progression, and the effects of drugs or therapies.

Fig.1 Human organoids

The complexity of organoid models arises from the combination of stem cells, extracellular matrices (ECM), and specific growth factors. These factors are critical to inducing the appropriate growth and differentiation of the cells into organ-like structures.

The Role of EGF in Organoid Construction

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) is a small polypeptide that plays a pivotal role in regulating cell growth, differentiation, and survival. It does so by binding to the EGF receptor (EGFR) on the surface of cells, initiating a cascade of intracellular signaling pathways that promote cell proliferation, migration, and survival. In the context of organoid development, EGF is essential for maintaining the self-renewal capabilities of stem cells and promoting their proliferation.

1. Promoting Cell Proliferation and Growth

One of the primary functions of EGF in organoid culture is promoting cell proliferation. In the early stages of organoid development, EGF stimulates the division of stem cells, ensuring a robust number of cells to form the initial organoid structure. Without sufficient cell proliferation, organoids would fail to develop into mature, functional tissues. EGF, along with other growth factors, plays a key role in maintaining the balance between cell renewal and differentiation, which is vital for generating organoids that resemble the complexity of actual organs.

2. Maintaining Stem Cell Characteristics

Stem cells in organoid cultures must retain their pluripotency or multipotency to produce differentiated progeny that mimic various cell types found in organs. EGF helps maintain the stemness of these cells, ensuring that they continue to self-renew and remain undifferentiated. In the absence of adequate EGF signaling, stem cells may prematurely differentiate or fail to expand, compromising the integrity of the organoid model.

3. Supporting Differentiation into Specific Cell Types

While EGF is essential for promoting stem cell proliferation, it also plays a role in the differentiation process. Depending on the organoid model, EGF can direct stem cells to differentiate into specific cell types, such as epithelial, endothelial, or neuronal cells. In some organoid protocols, EGF is used in combination with other growth factors to guide the differentiation of stem cells into tissues resembling the targeted organ. For example, in intestinal organoid models, EGF promotes the development of epithelial cells, which form the functional lining of the gut.

4. Influencing Organoid Morphogenesis

EGF not only regulates cell proliferation and differentiation but also contributes to the morphogenesis of organoids. As stem cells divide and differentiate, they need to organize themselves into specific structures. EGF aids in the formation of cellular layers and tissue architecture, which is essential for generating organoids that mimic the functional units of actual organs. Proper morphogenesis allows the organoids to carry out functions like nutrient absorption, hormone secretion, or toxin filtration, depending on the organ model being studied.

EGF in Different Organoid Models

The influence of EGF on organoid construction is not uniform across all organ types. The specific role of EGF varies depending on the organ being modeled and the stem cell type used. Below are some examples of how EGF is used in different organoid models:

1. Intestinal Organoids

In the development of intestinal organoids, EGF plays a crucial role in maintaining the epithelial stem cell population and promoting the differentiation of these cells into the specialized cell types found in the intestine. EGF helps create the proper microenvironment to support the growth of both the crypt and villus regions of the intestine. Additionally, EGF signaling is important for maintaining the self-renewal of stem cells located in the crypts.

2. Brain Organoids

In brain organoid cultures, EGF is often included in the culture medium to support the proliferation of neural progenitor cells. These progenitors give rise to the various neuronal and glial cell types in the brain. EGF assists in the expansion of these neural progenitors while allowing them to differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, which are necessary for modeling the complex structures and functions of the brain.

3. Liver Organoids

Liver organoid models also rely on EGF to maintain the proliferation of hepatocyte progenitors, which can differentiate into mature hepatocytes capable of performing critical liver functions, such as detoxification and metabolism. EGF helps maintain the regenerative capacity of these progenitor cells, which is key to modeling liver diseases and studying liver regeneration.

4. Lung Organoids

Lung organoids are another area where EGF is used to stimulate the growth of lung progenitor cells. In these models, EGF promotes the formation of epithelial cells that line the airways and alveoli. These epithelial cells are essential for studying respiratory diseases, drug responses, and the effects of environmental toxins on lung tissue.

The Impact of EGF on Organoid Research and Drug Development

The ability to generate organoid models that mimic human organs has vast implications for drug discovery, disease modeling, and personalized medicine. EGF’s role in creating robust, functional organoids is integral to the success of these applications.

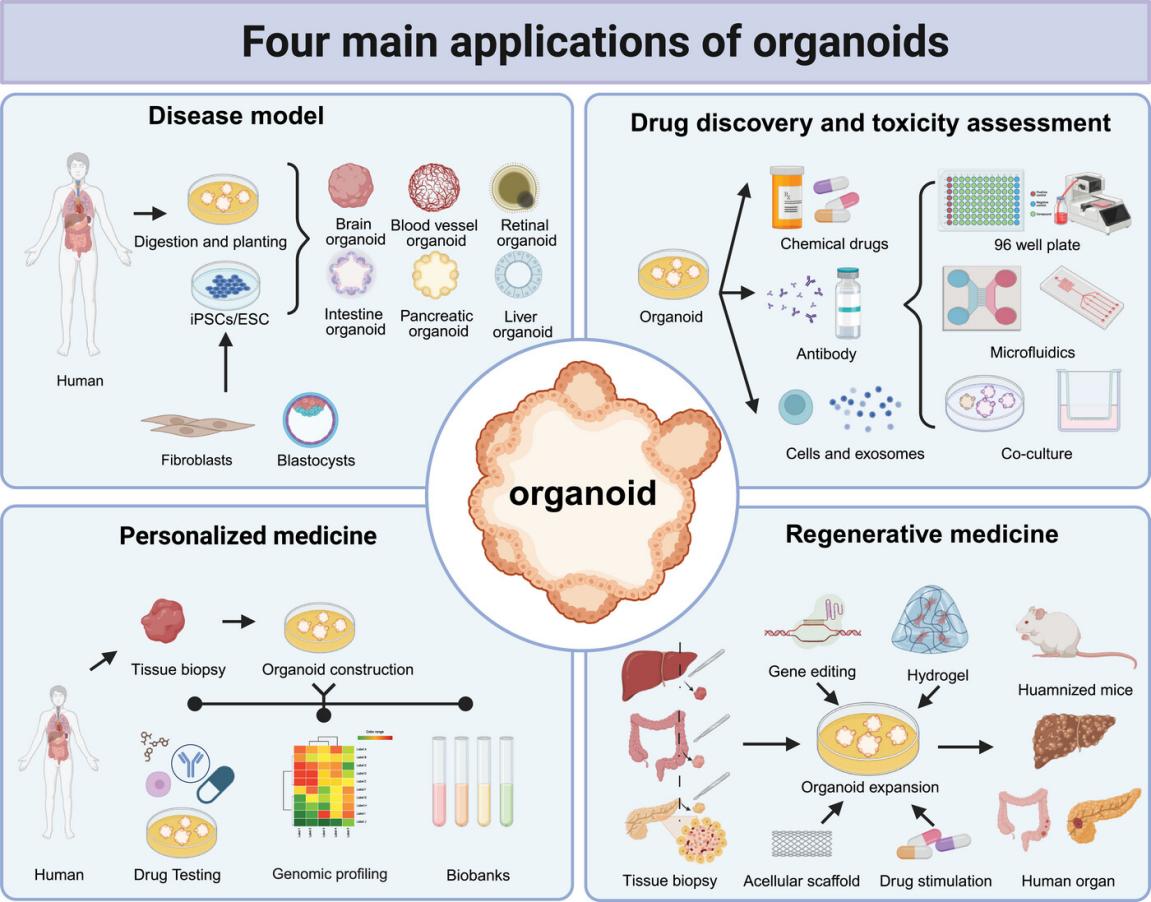

Fig.2 Four main applications of organoids

1. Drug Screening and Toxicity Testing

EGF-enhanced organoid models offer a platform for testing the effects of drugs on human tissues. By modeling the specific organ of interest, researchers can screen potential drug candidates for efficacy and safety in a way that is more reflective of human biology than traditional 2D cell cultures. For example, liver organoids can be used to study hepatotoxicity, while brain organoids can help evaluate the effects of neuroactive drugs. The inclusion of EGF ensures that the organoids remain viable and exhibit the correct cellular responses.

2. Disease Modeling

EGF plays a critical role in modeling diseases by enabling the growth of organoids that replicate disease conditions, such as cancer, fibrosis, or neurodegenerative disorders. Researchers can manipulate EGF signaling pathways in organoid cultures to study disease progression and develop targeted therapies. For example, in cancer research, organoids can be used to model tumors, and the effect of EGF signaling on tumor growth can be studied to identify potential therapeutic targets.

3. Personalized Medicine

Personalized medicine aims to tailor treatments to individual patients based on their unique genetic makeup. Organoids derived from patient-specific stem cells can be used to test how a patient’s cells respond to various treatments. EGF’s role in maintaining the growth and differentiation of these patient-derived organoids is essential for creating accurate models that reflect the patient’s disease and treatment responses.

Conclusion

Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) plays an indispensable role in the construction of organoid models by promoting cell proliferation, maintaining stem cell characteristics, supporting differentiation, and influencing organoid morphogenesis. Its inclusion in organoid culture protocols enhances the formation of organ-like structures that replicate the function and architecture of real organs. With the ability to generate complex, functional tissues, EGF-driven organoid models are advancing drug discovery, disease modeling, and personalized medicine. As organoid research continues to evolve, the role of growth factors like EGF will remain crucial in unlocking new possibilities for understanding human biology and improving healthcare outcomes.

References

- Lancaster, M. A., & Knoblich, J. A. (2014). Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science, 345(6194), 1247125. Link

- Sato, T., Vries, R. G. J., Snippert, H. J., van de Wetering, M., et al. (2009). Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt–villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature, 459(7244), 262-265. Link

- Clevers, H. (2016). Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell, 165(7), 1586-1597. Link

- Fujii, M., Shimokawa, M., Date, S., et al. (2016). Human intestinal organoids maintain self-renewal capacity and cellular diversity in vitro. Science, 346(6211), 1420-1423. Link

- Boj, S. F., Hwang, C. I., Baker, L. A., et al. (2015). Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell, 160(1-2), 324-338. Link