Unveiling the Future of Medicine: The Power of Organoids

Abstract

Organoids, three-dimensional structures grown from stem cells, have revolutionized biomedical research by mimicking the structure and function of real organs. These models are invaluable for disease modeling, drug testing, personalized medicine, and regenerative medicine. Despite their promise, organoid research faces challenges such as scalability, reproducibility, complexity, and ethical concerns. Technological advancements in microfluidics, bioprinting, and gene editing are paving the way for more sophisticated and applicable organoid models. The future of organoids is promising, with potential applications in personalized medicine and regenerative therapies, poised to significantly advance our understanding of human biology and improve healthcare outcomes.

Introduction

In recent years, the field of biomedical research has witnessed a groundbreaking development: the advent of organoids. These miniature, simplified versions of organs are grown from stem cells in a lab and have the unique ability to mimic the architecture and function of real organs. This remarkable advancement is not only opening new doors for scientific exploration but also revolutionizing the way we approach medical research and treatment.

Organoids are cultivated in three-dimensional cultures, which allow them to develop similarly to how organs do in the body. This ability to replicate the complex structure and activity of organs such as the brain, liver, and kidneys has profound implications for understanding human biology and disease. By using stem cells, scientists can create organoids that model specific diseases, offering an unparalleled opportunity to study the development and progression of conditions such as cancer, neurological disorders, and infectious diseases in a controlled environment.

The significance of organoids extends beyond disease modeling. In the realm of drug testing and development, organoids offer a more accurate and ethical alternative to traditional methods. They enable researchers to test the efficacy and safety of new drugs on human-like tissues without relying on animal models, which often fail to predict human responses accurately. Furthermore, organoids hold immense promise for personalized medicine. By generating organoids from a patient’s own cells, doctors can tailor treatments to the individual’s unique genetic makeup, potentially improving outcomes and reducing side effects.

Despite these exciting advancements, the field of organoid research is not without challenges. Scientists are continuously working to overcome limitations such as scalability, reproducibility, and the ability to fully replicate the complexity of human organs. Nevertheless, the potential of organoids to transform medicine is undeniable, heralding a future where treatments are more precise, personalized, and effective.

What Are Organoids?

Organoids are three-dimensional structures grown from stem cells that emulate the architecture and function of real organs. Unlike traditional two-dimensional cell cultures, organoids can develop multiple cell types, organize into distinct regions, and replicate some specific functions of their in vivo counterparts. This makes them invaluable tools for biomedical research, offering more physiologically relevant models for studying development, disease, and potential treatments.

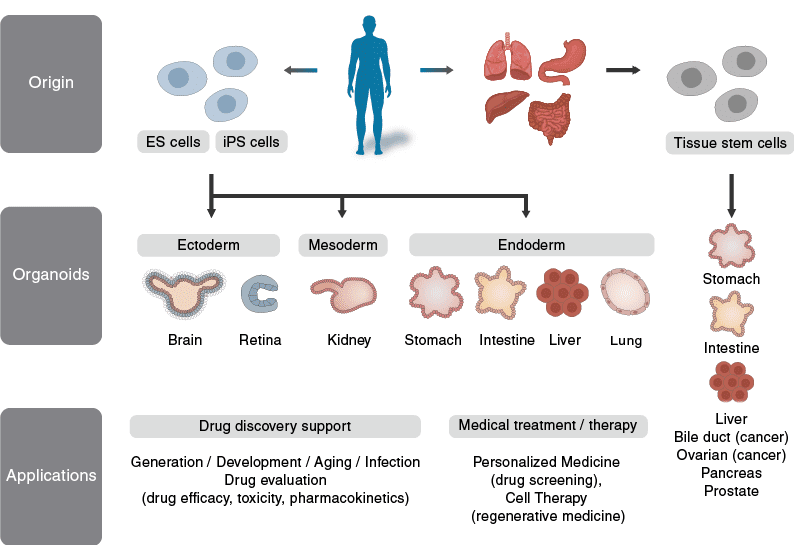

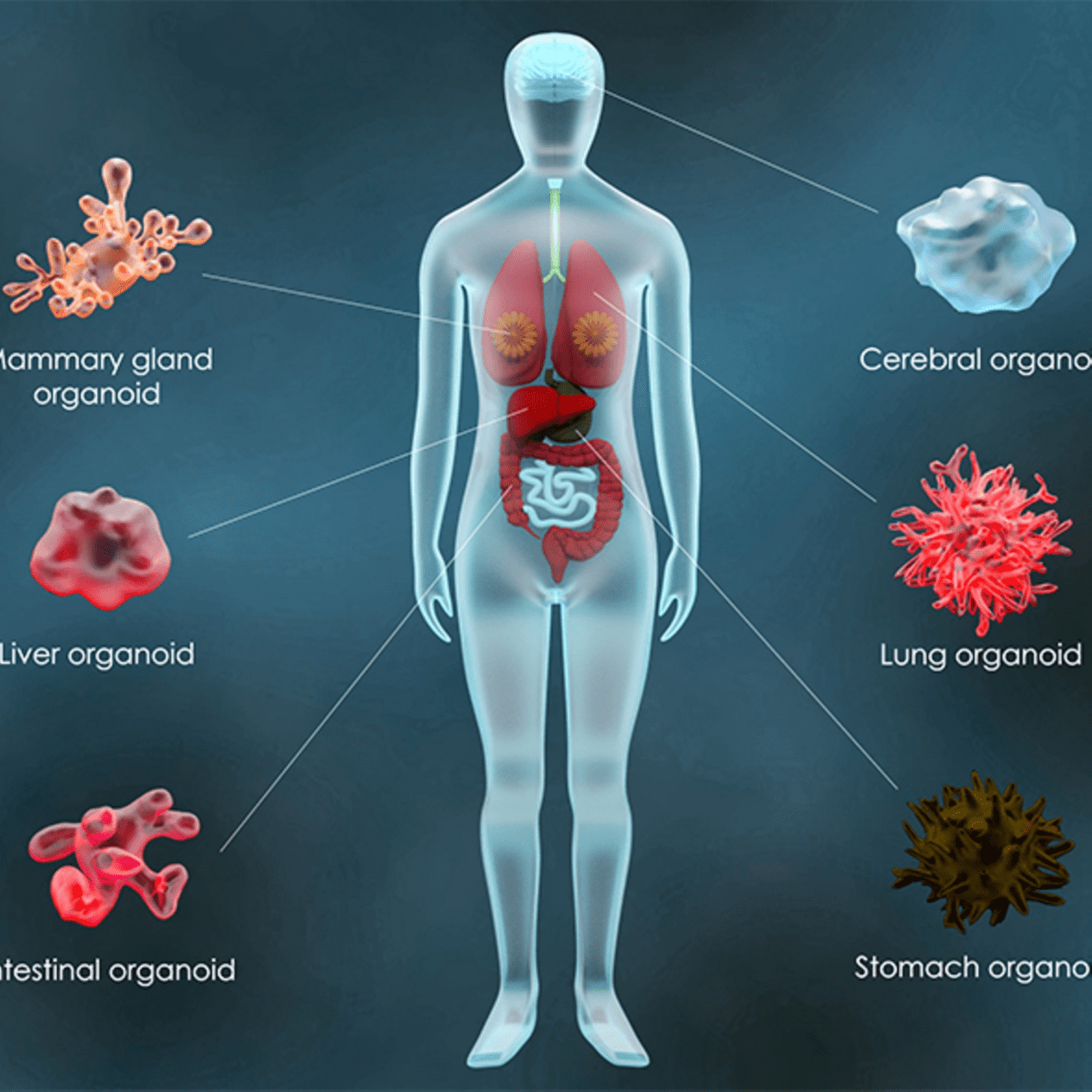

Fig.1 What Are Organoids?

The process of creating organoids starts with stem cells, which are cells capable of differentiating into various cell types. These stem cells are induced to form organ-specific cells through the use of growth factors and specific culture conditions. The result is a miniaturized, simplified version of an organ that still retains many of the key features of the full-sized organ. Organoids can be derived from embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), or adult stem cells, each type offering different advantages for research and therapeutic applications.

The Science Behind Organoids

The science of organoid development hinges on the remarkable ability of stem cells to self-organize and differentiate into specific cell types. This process is guided by carefully controlled environmental conditions and the introduction of signaling molecules that mimic the natural development processes occurring in the body.

Stem Cells: The foundation of organoid technology lies in the use of stem cells, which can be broadly categorized into embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). ESCs are derived from early-stage embryos and have the potential to develop into any cell type in the body. iPSCs, on the other hand, are created by reprogramming adult cells to a pluripotent state, providing a more ethical and accessible source of stem cells.

3D Culture Systems: To grow organoids, researchers use 3D culture systems that provide a supportive environment for stem cells to grow and differentiate. These systems often include matrices like Matrigel, which provides the structural support and biochemical signals necessary for cells to organize into complex structures.

Growth Factors and Signaling Molecules: The differentiation of stem cells into specific cell types and the formation of organoid structures are driven by the addition of growth factors and signaling molecules. These substances mimic the natural signals that guide organ development in the body. For example, to create brain organoids, researchers add specific factors that promote the formation of neural tissues.

Self-Organization and Differentiation: One of the most remarkable aspects of organoids is their ability to self-organize. When provided with the right conditions, stem cells can spontaneously arrange themselves into structures that resemble real organs. This process involves the differentiation of stem cells into multiple cell types and the organization of these cells into distinct regions that mimic the architecture of an organ.

Fig.2 The Story of Organoids

Applications of Organoids

Organoids, with their remarkable ability to mimic the structure and function of real organs, have revolutionized biomedical research and opened new avenues in various fields of medicine. Their applications span across disease modeling, drug testing, personalized medicine, and regenerative medicine.

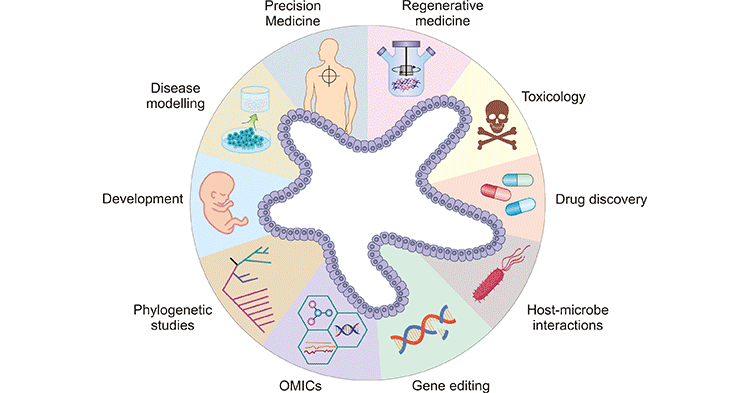

Fig.3 Applications of Organoids

Disease Modeling: One of the most significant applications of organoids is in disease modeling. Traditional two-dimensional cell cultures often fail to capture the complexity of human tissues, and animal models do not always accurately represent human biology. Organoids bridge this gap by providing a more physiologically relevant model. Researchers use organoids to study a wide range of diseases, including cancer, infectious diseases, genetic disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, brain organoids have been used to model neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

Drug Testing and Development: Organoids offer a more accurate and ethical alternative to animal models for drug testing. They enable high-throughput screening of drug candidates in a setting that closely mimics human tissues. This not only improves the relevance of preclinical studies but also reduces the need for animal testing. Organoids derived from different tissues can be used to assess drug toxicity, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics, providing a comprehensive understanding of how drugs will perform in the human body. For example, liver organoids are employed to study drug metabolism and hepatotoxicity, ensuring that new pharmaceuticals are safe and effective.

Personalized Medicine: The advent of organoids has paved the way for personalized medicine, where treatments can be tailored to an individual’s unique genetic makeup. By creating organoids from a patient’s own stem cells, researchers can study the specific characteristics of their disease and test different treatment options. This approach is particularly valuable for conditions like cancer, where organoids can be used to predict how a patient will respond to various chemotherapy drugs, allowing for the selection of the most effective and least toxic treatment regimen.

Regenerative Medicine: Organoids hold immense promise for regenerative medicine. They can potentially be used to repair or replace damaged tissues and organs. For example, researchers are exploring the use of intestinal organoids to treat patients with gastrointestinal diseases by transplanting lab-grown tissues into affected areas. Similarly, liver organoids could one day provide a source of transplantable tissue for patients with liver failure. Although the clinical application of organoids in regenerative medicine is still in its infancy, the potential benefits are vast.

Breakthroughs in Organoid Research

The field of organoid research has seen several groundbreaking advancements that have significantly enhanced our understanding of human biology and disease.

Brain Organoids and Neurological Research: In recent years, brain organoids have been used to model various aspects of brain development and disease. Researchers have successfully generated organoids that mimic the early stages of brain development, providing insights into developmental disorders such as microcephaly. Moreover, brain organoids have been instrumental in studying the effects of Zika virus infection on fetal brain development, demonstrating how the virus causes microcephaly by disrupting neural progenitor cells.

Cancer Organoids for Precision Oncology: Cancer organoids have emerged as powerful tools for precision oncology. By growing tumor organoids from patients’ cancer cells, researchers can study the genetic and phenotypic diversity of tumors, identify potential therapeutic targets, and test the efficacy of different drugs. This approach has already shown promise in tailoring treatments for colorectal, pancreatic, and breast cancers, among others.

Gut and Liver Organoids: Advances in gut and liver organoid research have provided new insights into gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Intestinal organoids have been used to model inflammatory bowel disease, allowing researchers to investigate the underlying mechanisms and test potential therapies. Liver organoids, on the other hand, have been employed to study liver fibrosis, hepatitis infections, and metabolic diseases, offering a platform for drug discovery and development.

Gene Editing and Organoids: The combination of organoid technology with gene editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 has opened new possibilities for studying genetic diseases. Researchers can introduce specific genetic mutations into organoids to create models of inherited diseases, enabling the study of disease mechanisms and the development of gene-based therapies. This approach has been used to model cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, and other genetic conditions.

Benefits of Using Organoids

The use of organoids in research and medicine offers numerous benefits that make them a superior model compared to traditional methods.

Physiological Relevance: Organoids closely mimic the architecture and function of real organs, providing a more accurate representation of human tissues. This makes them invaluable for studying complex biological processes and disease mechanisms.

Ethical Advantages: Organoids reduce the reliance on animal models, addressing ethical concerns associated with animal testing. This is particularly important for studying human-specific diseases and drug responses, where animal models often fall short.

High-Throughput Screening: Organoids can be used for high-throughput drug screening, allowing researchers to test large numbers of drug candidates quickly and efficiently. This accelerates the drug development process and reduces costs.

Personalized Medicine: By creating organoids from a patient’s own cells, researchers can develop personalized treatment plans that are tailored to the individual’s genetic makeup and disease characteristics. This approach has the potential to improve treatment outcomes and reduce side effects.

Regenerative Medicine: Organoids hold promise for regenerative medicine, offering the potential to repair or replace damaged tissues and organs. This could provide new treatment options for patients with chronic diseases or organ failure.

Despite the numerous benefits, there are challenges associated with organoid research. These include issues related to scalability, reproducibility, and the ability to fully replicate the complexity of human organs. Nevertheless, the progress made so far is promising, and continued advancements in this field are likely to have a profound impact on biomedical research and healthcare.

Challenges and Limitations

While organoids have revolutionized biomedical research, their development and application come with several challenges and limitations. These obstacles need to be addressed to fully harness the potential of organoids.

Scalability: One of the primary challenges is scalability. Growing organoids is a labor-intensive process that requires precise control over culture conditions. Producing organoids in large quantities for high-throughput applications or clinical use remains a significant hurdle. Standardizing protocols and developing automated systems for organoid culture are essential steps towards overcoming this challenge.

Reproducibility: Reproducibility is another critical issue. Variability in the growth conditions, stem cell sources, and differentiation protocols can lead to inconsistencies in organoid development. This variability affects the reliability of organoids as models for disease and drug testing. Establishing standardized procedures and quality control measures is crucial for improving reproducibility.

Complexity and Maturation: Organoids often lack the full complexity and maturity of real organs. They may not fully replicate the diverse cell types, intricate architecture, and functional integration found in human tissues. For instance, brain organoids do not yet fully mimic the connectivity and functionality of a mature human brain. Researchers are exploring advanced techniques, such as co-culture systems and bioengineering approaches, to enhance the complexity and maturation of organoids.

Vascularization: A significant limitation of current organoid models is the lack of a vascular system. In real organs, blood vessels provide nutrients and oxygen to cells and remove waste products. The absence of vascularization in organoids limits their size and longevity, affecting their physiological relevance. Integrating vascular networks into organoids is a major area of ongoing research.

Ethical and Regulatory Issues: The use of stem cells, particularly embryonic stem cells, raises ethical concerns. Moreover, the development of organoids with human-like features, such as brain organoids, poses ethical and regulatory challenges. Addressing these issues requires careful consideration of ethical guidelines and regulatory frameworks.

The Future of Organoids

Despite these challenges, the future of organoids holds immense promise. Advances in technology and scientific understanding are paving the way for more sophisticated and applicable organoid models.

Technological Innovations: Emerging technologies such as microfluidics, bioprinting, and gene editing are expected to enhance the development of organoids. Microfluidic systems can provide precise control over the microenvironment, improving the growth and differentiation of stem cells. Bioprinting allows for the creation of complex tissue structures by layering different cell types in a defined architecture. Gene editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 enable precise manipulation of genetic material, facilitating the creation of disease-specific organoid models.

Integration with Other Models: Combining organoids with other models, such as organ-on-a-chip systems, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of human physiology and disease. Organoids can be integrated into microfluidic devices to study interactions between different tissues and organs, simulating the complexity of the human body.

Clinical Applications: As organoid technology advances, its translation into clinical applications is becoming more feasible. Organoids could be used for personalized medicine, where patient-specific organoids are employed to test drug responses and predict treatment outcomes. In regenerative medicine, organoids may serve as a source of transplantable tissues or be used to develop new therapies for repairing damaged organs.

Conclusion

Organoids represent a transformative advancement in biomedical research, offering a more accurate and ethical alternative to traditional models. Their ability to mimic the structure and function of real organs has opened new avenues for studying disease, testing drugs, and developing personalized treatments. However, challenges related to scalability, reproducibility, complexity, and ethical issues need to be addressed to fully realize their potential. The future of organoids is bright, with technological innovations and integration with other models driving progress towards more sophisticated and clinically relevant applications. As these challenges are overcome, organoids are poised to play a central role in advancing our understanding of human biology and improving healthcare outcomes.

References

- Clevers, H. (2016). Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids. Cell, 165(7), 1586–1597. DOI

- Lancaster, M. A., & Knoblich, J. A. (2014). Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science, 345(6194), 1247125. DOI

- Huch, M., & Koo, B.-K. (2015). Modeling mouse and human development using organoid cultures. Development, 142(18), 3113–3125. DOI

- Sato, T., & Clevers, H. (2013). Growing self-organizing mini-guts from a single intestinal stem cell: Mechanism and applications. Science, 340(6137), 1190–1194. DOI

- Lancaster, M. A., Renner, M., Martin, C.-A., Wenzel, D., Bicknell, L. S., Hurles, M. E., … & Knoblich, J. A. (2013). Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature, 501(7467), 373–379. DOI

- Eiraku, M., & Sasai, Y. (2012). Self-formation of layered neural structures in three-dimensional stem cell cultures. Cell Stem Cell, 10(6), 771–785. DOI

- Fatehullah, A., Tan, S. H., & Barker, N. (2016). Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nature Cell Biology, 18(3), 246–254. DOI